The Marred History of the Hunley

© Copyright 2017 by Dr. E. Lee Spence for composition, compilation and images.

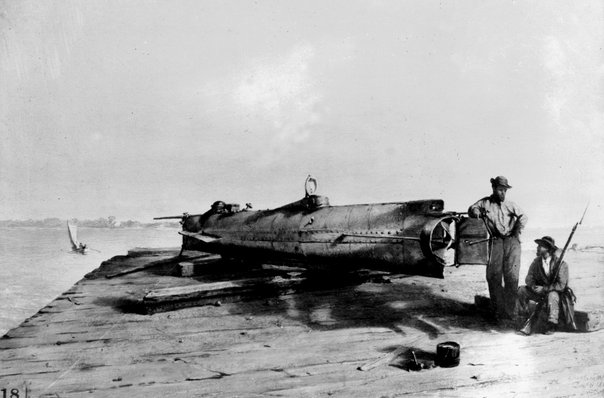

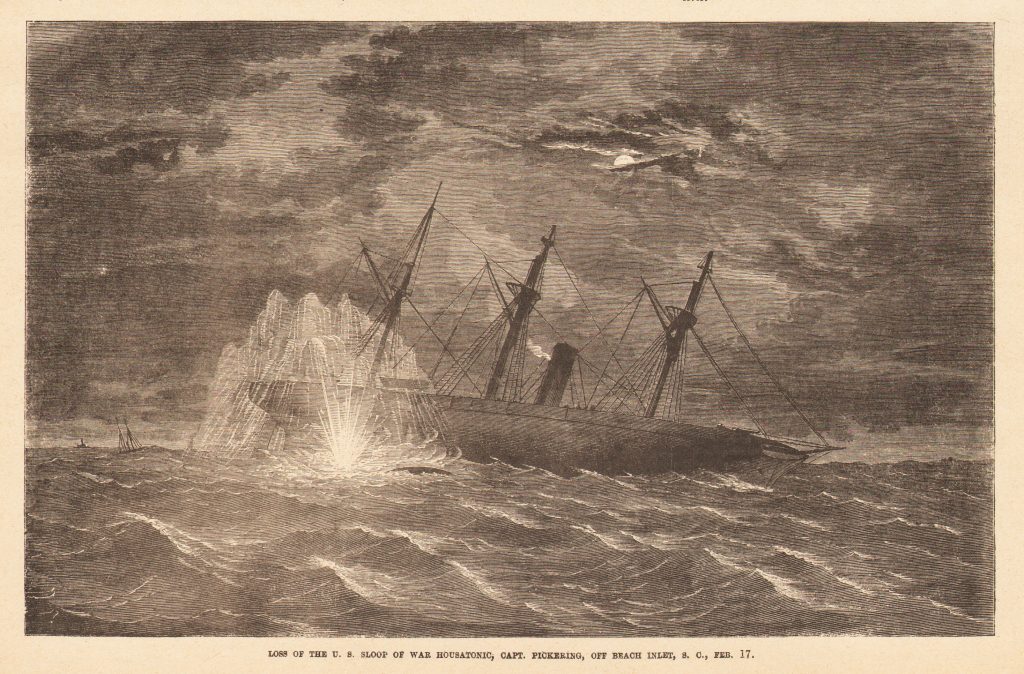

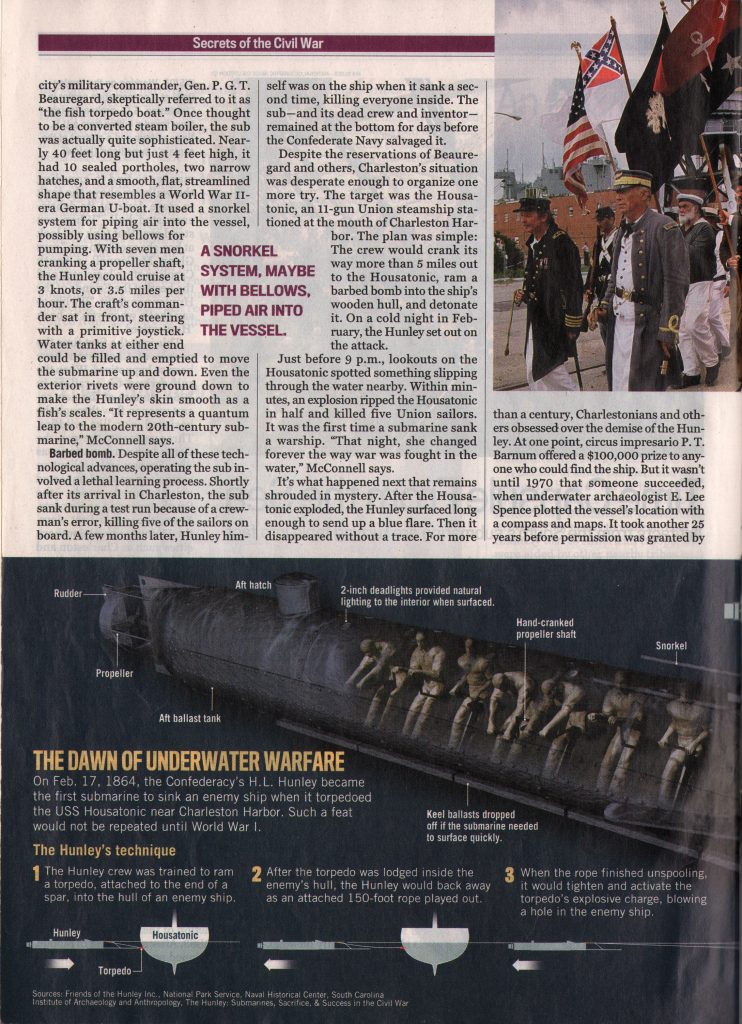

At least since the days of Alexander the Great, navies, inventors, and rulers of empires dreamed of underwater boats that might be used in naval warfare. But it was not until February 17, 1864, when the Confederate torpedo boat H.L. Hunley became the first submarine in the history of the entire world to sink an enemy warship that the dream was truly realized.

Although hand-cranked and under 40 feet long, the Hunley was a true submarine fully capable of submerging for long periods of time and could go entirely under another vessel, which she did during a practice trial in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina.

Following the Hunley’s successful attack against the heavily armed, 205 foot long, United States steam-powered sloop-of-war Housatonic, the Hunley was lost along with her crew of eight before she could return to her base on Sullivan’s Island. Almost immediately after her loss the U.S. Navy, using grappling hooks and divers, searched for 500 yards all of the way around the sunken warship without finding any trace of the sub. Countless others searched for her — some for a rumored reward, which would have been today’s equivalent of over a million dollars; others for fame and glory; and some simply for their love of history. For more than a century the Hunley’s location remained a one of the great, unsolved mysteries.

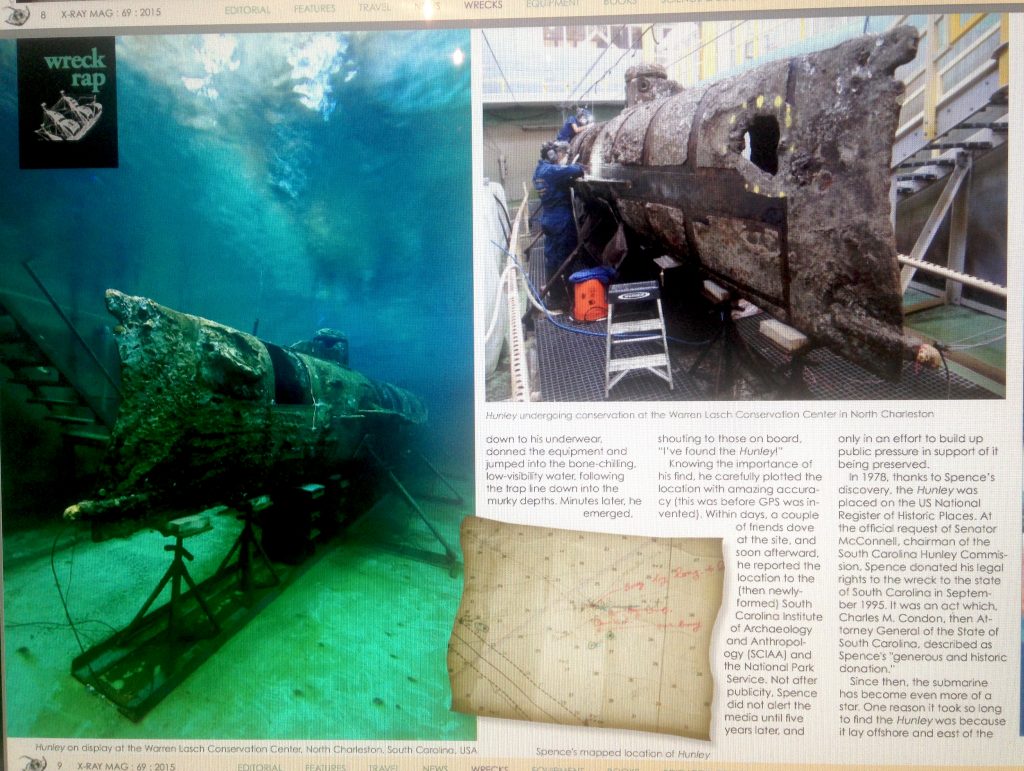

The Hunley’s discovery was described by Dr. William Dudley, Director of Naval History at the Naval Historical Center as “probably the most important (underwater archaeological) find of the (20th) century.” The tiny sub and her contents have been valued at more than $40 million, making her discovery and subsequent donation one of the most important and valuable private contributions made to South Carolina. But, for some, the discovery itself remains mired in controversy.

Although novelist Clive Cussler is credited by some with discovering the Hunley in 1995, an examination of the facts bear out that I discovered the wreck of this historic submarine in 1970, and its location had not been subsequently lost and had, in fact, been widely published. Even though the wreck was over three nautical miles from the nearest shore and I was not legally required to report my discovery to the State, it was of such importance that I wanted my discovery properly recorded, so I immediately notified Dr. Robert L. Stephenson, State Archaeologist and Director of the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology & Anthropology (SCIAA) of my find. But, having dealt with Dr. Stephenson on other wrecks and having reason to believe he was both jealous and unscrupulous, and might try to grab control and all of the credit for himself, I tried to play down how sure I was of the wreck’s identification.

However, I did trust Ron A. Gibbs, a close friend and Curator of Armed Forces History at the National Park Service (NPS) who had dived with me on several other Civil War era shipwrecks that I had discovered, including the blockade runners Georgiana, Mary Bowers, Constance, Flamingo, Colt, Presto, etc. So, I contacted him and, concealing nothing, I explained everything and asked him for his advice. Gibbs introduced me to NPS underwater archaeologist Dr. George Fischer who told me that the United States owned the wreck of the Hunley, as it was property formerly belonging to the Confederate States of America. According to my attorneys he was incorrect, but I will address that later. Dr. Fischer said the General Services Administration (GSA) was in charge or all former Confederate property and that they would not give permission to dig up or raise it unless the work was done through a university or a 501-C3 tax exempt, non-profit organization. In 1972, at Dr. Fischer’s suggestion, and with his agreeing to serve on its Board of Advisers, I formed the Sea Research Society and then applied to the GSA for permission to raise the Hunley and donate it to a museum.

The Society’s founding board members also included: Mendel L. Peterson, Curator of the Division of Historic Archaeology at the Smithsonian Institution; Luis Marden, Senior Editor, National Geographic Magazine; Frederic Dumas, French underwater archaeologist who was part of Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s original team; Anders Franzen, Swedish underwater archaeologist and discoverer of the Swedish warship Vasa; Ron A. Gibbs, Curator Armed Forces History, National Park Service; Paul Tzimoulis, Publisher, Skin Diver magazine; Ed Bearss, Senior Historian, National Park Service; Robert F. Marx, underwater archaeologist and shipwreck historian; Peter Throckmorton, “discoverer of the oldest known shipwreck;” Pablo Bush Romero, President, CEDAM (the Mexican underwater exploration group); Alan B. Albright, formerly of the Smithsonian and then with the Caribbean Research Institute; and others of similar note. Virtually all were published authors and internationally known for their work with shipwrecks. Several have been described as the “father of underwater archaeology.” I mention these people to properly credit them and so the reader will understand who was working with me in my efforts to get permission to raise the Hunley. Unfortunately, most of these outstanding men are now deceased. At the time I was Underwater Archaeology Editor for Diving World magazine, which was the official publication of the National Association of Underwater Instructors (NAUI), and I served both on the Board and as President of the Sea Research Society. For purely political reasons and even though he was not an underwater archaeologist, I asked South Carolina State Archaeologist Dr. Stephenson to serve on the board and he accepted. I would only learn decades later, that Dr. Stephenson used his position on the board to sabotage my efforts by writing and trying to dissuade others from working with me.

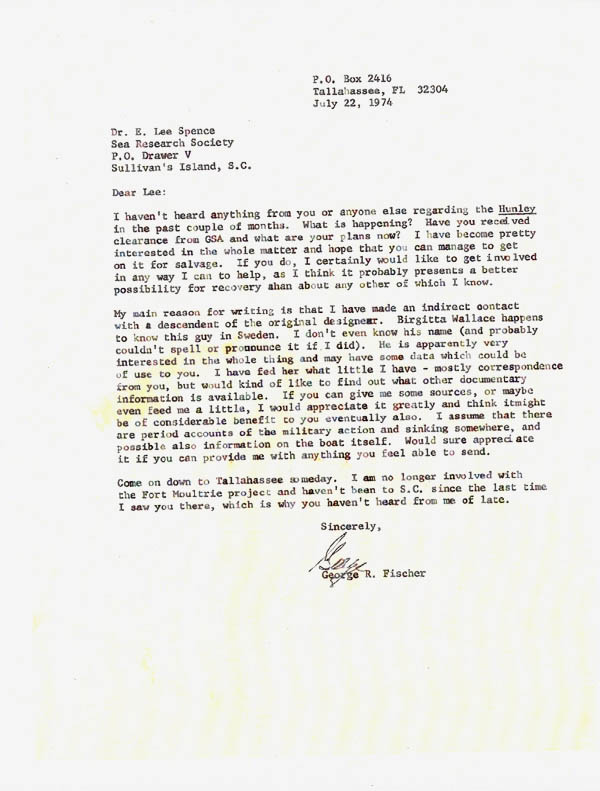

As shown here, Dr. Fischer continued his interest in the Hunley and his desire to be involved in the project even after he left the National Park Service.

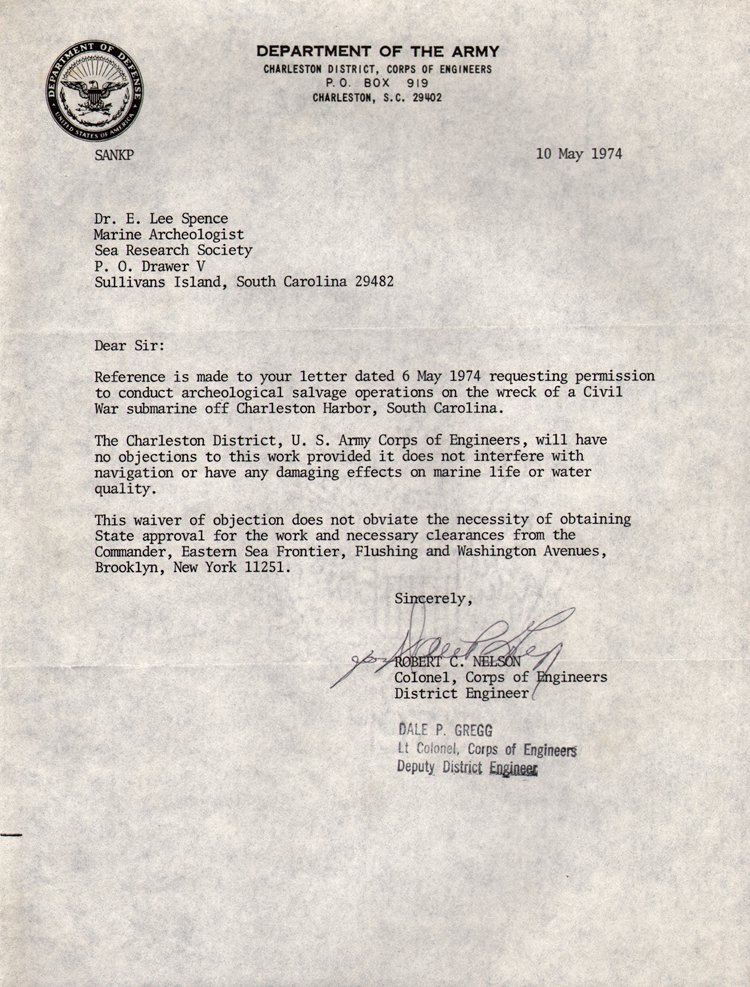

Dr. Fischer advised me that because the wreck of the Hunley was located in navigable waters, I would need permits and/or clearances from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Navy. After furnishing those two organizations with copies of my various charts and maps showing the Hunley’s correct location, and an acceptable working plan, both the Corps and the Navy gave the Society their approval for the work to go forward.

This waiver made clear that I still had to get other approvals and clearances before starting the work.

The first time I went back to the wreck site was a month or two after I found it and the wreck had already reburied. In 1971 I borrowed a proton magnetometer and, with the help of Mike Roberts and David McGeehee, I was able to relocate the wreck and get more angles and ranges for its location. The following picture is of me with the magnetometer.

This 1971 picture, taken by David McGeehee or Mike Douglas, shows me with the magnetometer we used to relocate the Hunley after it was reburied by shifting sands.

On a number of occasions in the early 1970s, I met with Senator Strom Thurmond, who years earlier had secured me an appointment to the Merchant Marine Academy; and with Senator Ernest Hollings, who I considered a personal friend and who was also a diver. Both senators endorsed my work and throughout that time I kept them updated with my continuing efforts to secure permission to salvage the Hunley. Senator Hollings even suggested that one of his aides serve on the Society’s Board as his liaison, which I immediately agreed to.

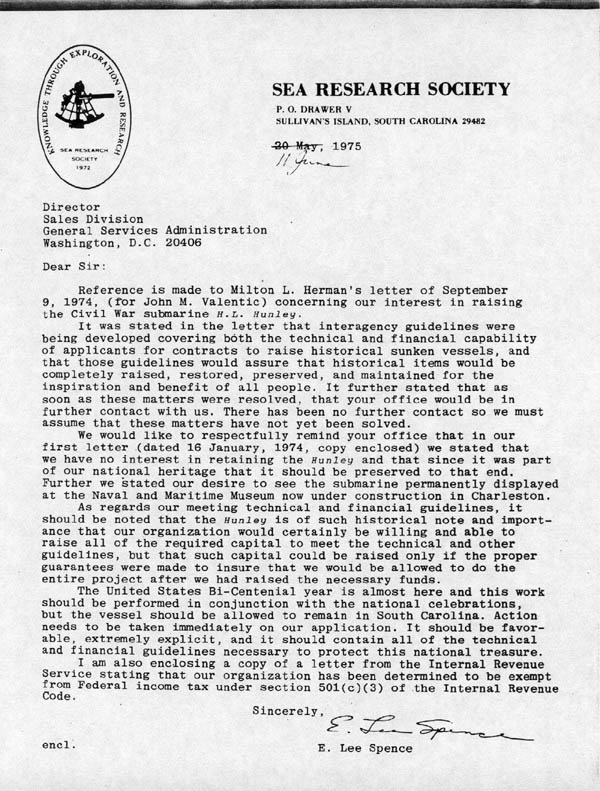

This letter to GSA shows that Sea Research Society was willing to comply with the interagency guidelines that were being developed, but that timing was critical if the Society was to take advantage of the upcoming Bi-Centential to start the work.

Even though the Society immediately paid the GSA a permit fee in the full amount the GSA requested, the GSA kept delaying and never issued the sought after and long promised salvage permit. The GSA ultimately returned the fee saying they were in the process of establishing new rules and regulations for such work. I now suspect it was really due to the then hidden machinations of Dr. Stephenson, who in 1975 physically assaulted me when I calmly questioned his bias towards me.

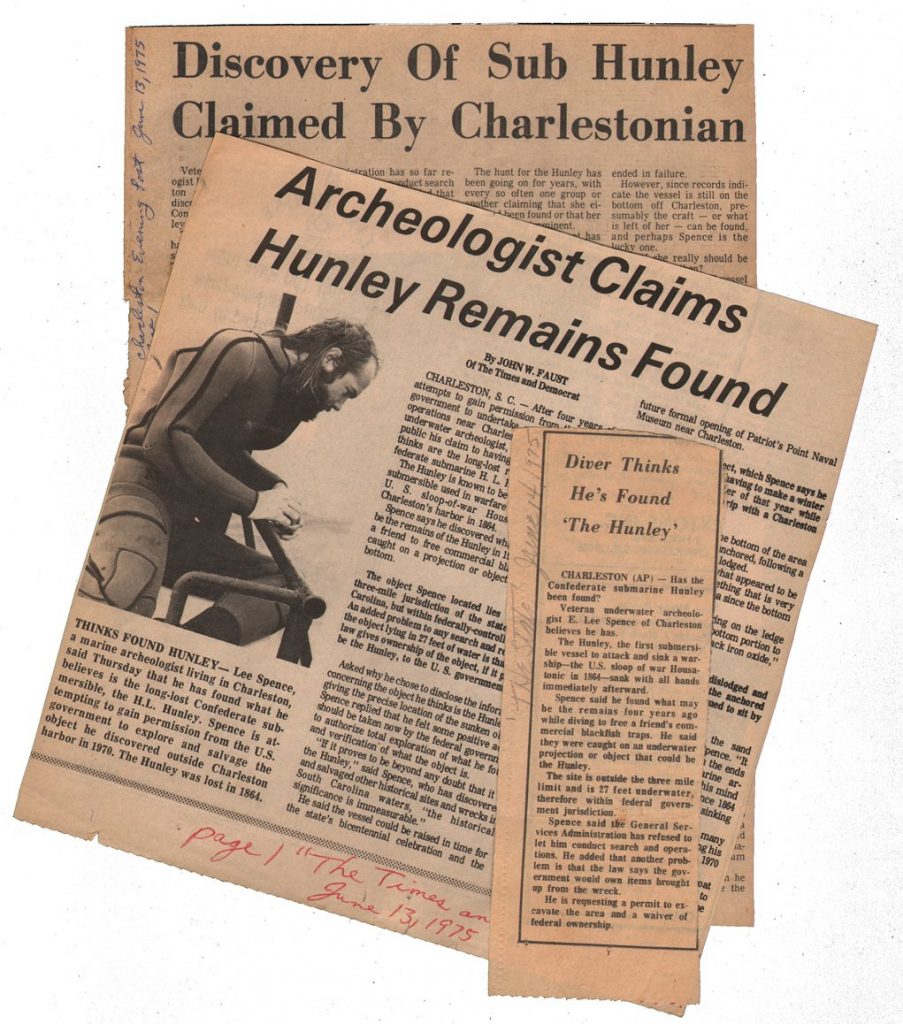

Although I reported my discovery to the State Archaeologist 1975 and immediately started working through what were considered the proper channels to get permission to raise the Hunley, I did not seek publicity, which shows it was not some publicity stunt, like the ones Cussler has bragged about in writing that he pulled off long before he got involved in the Hunley. The first news stories about my discovery came out in June of 1975, and I went to the media then only to put pressure on the government to act of the Society’s requests to raise the wreck.

In 1975, after years of waiting for GSA to process the Society’s application to salvage the Hunley, I finally went to the media in hopes that public pressure would spur GSA to action. My years of holding back news of my discovery of the Hunley from reporters, who were already writing about my other shipwreck discoveries, shows I wasn’t claiming I had discovered it just to get free publicity. Until I felt I needed to get the public involved, I had actually taken active steps to hide much of what I was doing from the press. Perhaps for comparison this is a good time to mention that Cussler held a press conference to announce his claims within weeks of his alleged discovery in 1995.

In 1976 someone at the National Park Service, I presume Dr. Fischer but perhaps not, submitted the Hunley for placement on the National Register of Historic Places. Two years later, on the basis of my discovery, the Hunley was officially placed on that list, which effectively meant that the government had officially recognized my discovery, as a wreck cannot legally be placed on that list unless its location is known. After that, anyone else’s claim to have discovered the Hunley, seems to me little or no different from their visiting Washington D.C. and afterwards claiming they had discovered the White House.

In 1979, using historical records showing that the Confederate government had confiscated the Hunley from her private builders without any sort of due process or payment for the submarine, I argued with my attorneys that ownership of the Hunley never legally passed to the United States at the end of the Civil War. Nor had it been captured, so it wasn’t a prize of war. They agreed with me.

In 1980, I filed a suit in Federal District Court in Charleston, South Carolina, claiming ownership of the Hunley. I claimed it under both the law of salvage and the law of finds. I also requested that the U.S. Marshals Office arrest the wreck, much as had been done with the wreck of the Atocha a few years before. So they couldn’t later say they didn’t know about my claim of ownership, I had both the State of South Carolina and the United States served as interested parties.

The State of South Carolina chose not to intervene. The United States government intervened in the case, but did not dispute either my discovery or my ownership. The United States’ attorney took the position that the wreck was outside of the jurisdiction of the U.S. Marshals Office, so it could not go to my site and arrest the wreck. According to my attorneys, that was good news for me, as the wreck would have been in their jurisdiction if the federal government had been the owner of the Hunley. The U.S. attorney saying that the wreck was out of the U.S. Marshals’ jurisdiction was a tacit admission by the United States that it didn’t have any legal rights to the Hunley. So, having filed public notice of the Hunley’s discovery and no heirs or others coming forward to dispute my discovery or to claim ownership of the submarine, my attorneys advised me to drop the suit, as, by the government’s failure to dispute my discovery and ownership claims, I had already become the de facto legal owner.

But, ownership of the wreck did not automatically mean I could salvage it because it was now on the National Register of Historic Places and that came with a lot of restrictions. In addition to those restrictions, I wasn’t about to raise the Hunley in a manner that didn’t meet the appropriate archaeological protocols. And, over the years, I had come to realize that to do everything correctly would cost many millions of dollars. My best estimate was it would cost at least twenty million dollars to raise and preserve and I simply didn’t have that kind of cash, and, despite my continued efforts, I couldn’t get others interested in footing the bill.

Throughout the 1980s it seemed to me that people and universities just didn’t want to be associated with anything that might make them look like they were honoring or placing importance on anything related to the Confederacy, which was so closely tied to slavery. What was really frustrating was that I couldn’t get anyone at the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology & Anthropology to even visit the site with me. However, I wasn’t surprised as SCIAA hadn’t bothered diving on the wreck of the Civil War blockade runner Georgiana, which I had discovered in the 1960s, even though my company’s original salvage license for that site, which was issued in 1968, was the very first salvage license ever given out by the State, and by law they weren’t to give out more licenses than they could properly supervise. In fact, it would not be until 2010 or later that SCIAA archaeologists finally made their first dives on the Georgiana. That was a shame because contemporary accounts described the Georgiana as not only having a million dollar cargo consisting of merchandise, munitions, and medicines, but as being the most powerful Confederate cruiser. And, some of the first underwater archaeology ever done on a historic shipwreck in North America had been done by my team on that wreck and we could have used their advice and help.

Published in 1984 by the Sea Research Society, these two volumes are just one of the many non-fiction books that I have written about shipwrecks. The first volume includes a chapter that tells of my discovery of the Hunley.

During the early to mid 1980s, much of my time was taken up with other projects ranging from searches I was doing off Cape Romain, South Carolina, that resulted in a number of new discoveries, to my archival study of thousands of shipwrecks sunk off South Carolina and Georgia in the period between 1521 and 1865. That research took literally years of my time. Incidentally, that study, which was published by the Sea Research Society, was largely paid for out of my pocket, but it was partially funded by the South Carolina Committee for the Humanities; the National Endowment for the Humanities; the College of Charleston; and the Savannah Ships of the Sea Museum.

Most of 1988-89 was occupied with my ultimately successful efforts to prove that a relatively unknown Charleston banker and shipping magnate, George Alfred Trenholm, who’s blockade running efforts earned today’s equivalent of over a billion dollars, was the historical basis behind Rhett Butler in Gone With The Wind. Trenholm had also been the person that had offered a huge reward for the sinking any of the warships used in the blockade of Charleston, which was why the original owners of the Hunley had shipped the submarine to Charleston.

Shortly after Hurricane Hugo struck the South Carolina coast in September of 1989, I met with officials at National Geographic Society (NGS), showed them my evidence, and discussed my belief that the hurricane might have uncovered the wreck, which had only been partially exposed when I discovered it and it had been entirely buried when I returned a few weeks later. National Geographic agreed to do an expedition with me. Our hope was the wreck had been uncovered by Hugo. If so, we could take pictures of it without having to get permits to dig it up. Being uncovered was considered important because even though I was the legal owner, without permission to do dredging at the site, I couldn’t legally dig up the wreck. If the wreck was exposed and we got pictures, NGS felt it would afterwards be easy for them to get permits for raising it. The expedition was delayed by the death of Al Chandler, NGS’ head of Special Projects, who they had placed in charge of their role in the expedition. Chandler was replaced by Claude E. “Pete” Petrone, but the expedition was again delayed by the illness and death of Petrone’s mother. During that delay a researcher, who NGS had hired to go over the historical data that I had furnished them, came to the conclusion that the Hunley had probably been scrapped along with the Housatonic after the Civil War and thus no longer existed, or at least would not be at the location that I reported, as my location was well within the area that had been searched by the U.S. Navy. NGS’ researcher was obviously wrong, but I was unable to convince the people that mattered otherwise. NGS apparently called off the expedition in 1990, but failed to actually tell me that for at least another year. By then the wreck, if it was exposed by Hugo, had been completely reburied by the shifting sands. From 1992 through 1994, I served as Chief of Underwater Archaeology for the Colombia Archipelago of Providencia Y San Andreas, off the coat of Nicaragua, so I had little time to pursue the Hunley, but I still tried to find a way to get the funding to raise her.

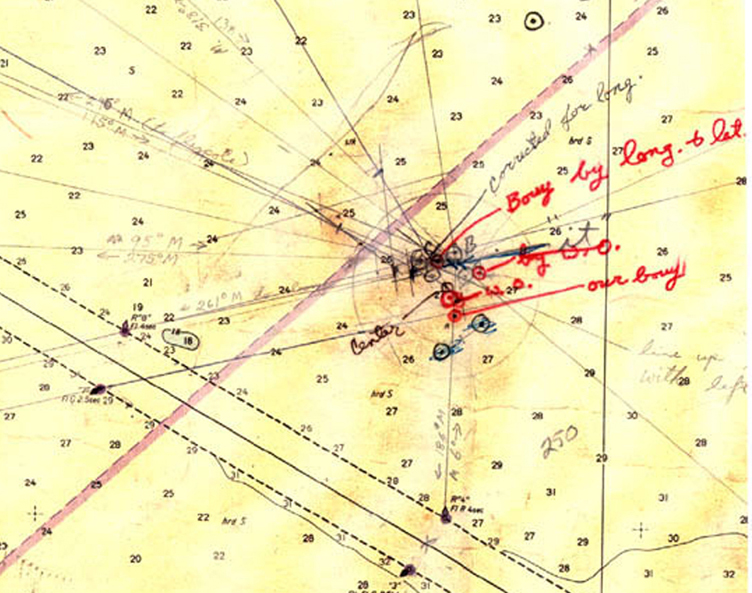

1979 Nautical Chart annotated by Spence. An arrow marked with the word center points to the center of the area that Spence later filed with his 1980 federal court claim against the Hunley. Another arrow, marked with the word “it” in quotes, points to an “X” marking the Hunley’s actual location. This chart was published in Spence’s 1995 book several months prior to Cussler’s divers alleged discovery.

In January of 1995, I published my book Treasures of the Confederate Coast that included a chart on which I had marked the Hunley’s correct location with an “X.” Realizing the Hunley’s location would now not only be known to anyone who thought to check the National Register, but by everyone who bought my book, I convinced Petrone and Mike Freeman, an underwater photographer who worked with National Geographic to agree to go to my wreck site with me. If it was exposed, we would use Freeman’s cameras to take the first pictures of the wrecked sub. But, since each time that I had returned to the site after my original discovery, it had been entirely buried, Petrone agreed to bring a ground penetrating radar and/or a sub-bottom profiler. Even if the Hunley was buried we expected to be able to get radar or sonar images of the wreck. Exactly one week before we were to go offshore, Freeman’s wife called me to say that he had died that morning. It was a terrible loss, not because of the timing, but because Mike Freeman was one of my oldest and dearest friends.

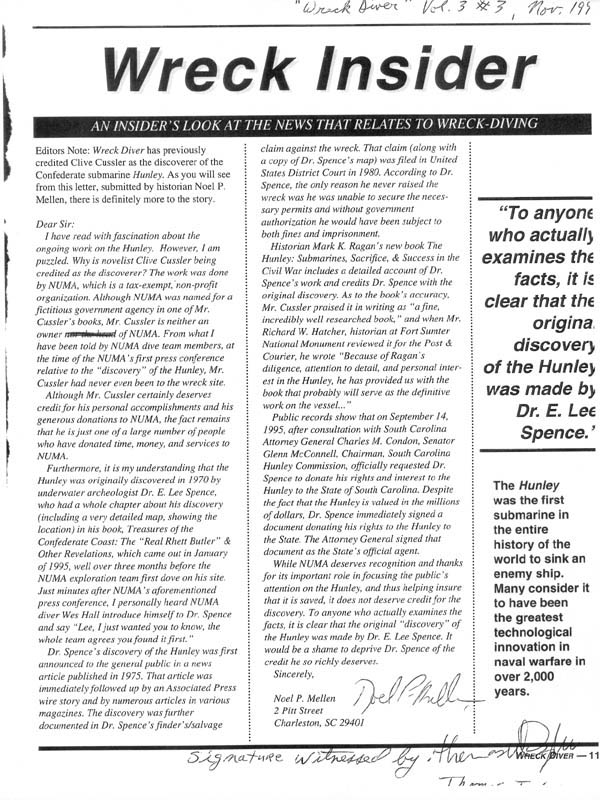

In April of 1995, divers who were officially part of an expedition that was initiated and directed by SCIAA underwater archaeologist Dr. Mark Newell, went to the wreck site, dug it up, and took the first pictures of the wreck of the Hunley. It was quite an accomplishment. Dr. Newell’s expedition had been funded in part by Cussler through his organization NUMA, so it is sometimes referred to as a joint SCIAA/NUMA expedition. Almost immediately, Cussler had organized a press conference and invited the New York Times and other media. At Cussler’s press conference, which Dr. Newell learned of only by chance, Cussler took virtually all of the credit for the “discovery.” One of the divers Cussler introduced as finding the wreck, afterwards came up to me, introduced himself, and in front of Charleston historian Noel P. Mellen said he just wanted to shake my hand, and added “the whole team agrees you found it first.” I was unable to get him to repeat what he said to a reporter. Mellen later wrote that he had witnessed the conversation.

Charleston Historian Noel P. Mellen wrote this letter, which was published in Volume 3, #3 of Wreck Diver. In his letter Mellen tells of personally hearing diver Wes Hall, who was part of the alleged 1995 Hunley discovery, tell Dr. Spence that “the whole team agrees you found it first.”

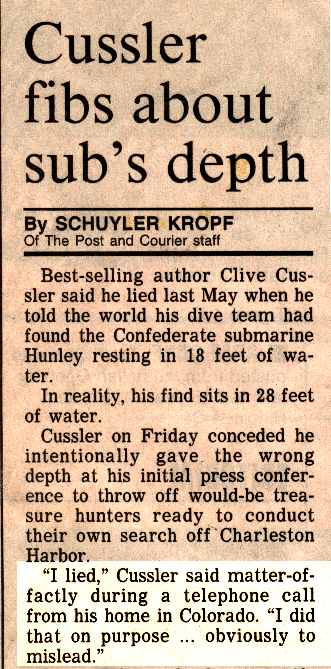

Cussler misrepresented the Hunley’s location by falsely claiming it was in just 18 feet of water well inshore of the wreck of its victim, the USS Housatonic, while my location was in 27 feet and about three hundred yards offshore (east) of that wreck. You might wonder why Cussler would lie about the wreck’s location. It certainly wasn’t to protect the site as my location was already published, and he could have simply remained silent if he was worried about looters. I think the answer is pretty clear. The difference in depths made it look like our locations were well over a mile apart. I suspect that if Cussler had admitted that the wreck was at my published location, the reporters would have laughed at his discovery claims. But, because “seeing is believing,” and he had pictures and I didn’t, Cussler was able to count on the reporters believing him. I didn’t have pictures because the day I found it I didn’t even own a camera capable of taking a picture in such limited visibility. And, by the time I did own one the shifting sands had recovered the wreck. I wasn’t willing to disturb an archaeological site just to get pictures, so virtually all of the media believed Cussler’s absurd discovery claims.

Most of the reporters, who seemed impressed by the author’s celebrity, ignored the fact that he made up stories for a living and used to be in the PR business. And, they didn’t correct their error in crediting Cussler with the discovery even after he finally admitted to reporter Schuylar Kropf that he had “lied” about the Hunley’s location. I certainly don’t know why, but Kropf was one of those who kept crediting Cussler as the discovery. Perhaps it was because Kropf had become the reporter most closely associated with the Hunley story and he didn’t want to admit that for a year he had been crediting the wrong person with its discovery. I guess its possible that Kropf truly believed Cussler had really found it, but my personal opinion is that Kropf, who had become friends with the wealthy celebrity, wanted Cussler’s cooperation and endorsement for a book that Kropf eventually co-authored on the Hunley. But, I view anything crediting Cussler with the discovery as revisionist history, no better than propaganda or fake news.

Clive Cussler’s admission that he “lied” as highlighted in this short article should have sufficient to discredit his discovery claims with respect to the Hunley, as had he told the truth from the beginning, anyone comparing his location with my already published location, would have immediately realized that they were one and the same, and I would have been credited.

The purple area on this map indicates the only waters 18? deep located between the wreck of the Housatonic and Sullivan’s Island. This is where Cussler claimed the SCIAA/NUMA expedition discovered the Hunley. That was not true. The Hunley was later determined by SCIAA & NPS to be in 27? of water at the spot marked by the red dot in the yellow rectangle. My location, as I had plotted it on two different maps in the 1970s, falls under that red dot. In other words, I told the truth and I correctly mapped and reported the location, while Cussler initially did not.

The purple area on the above map is the general area where Cussler first told the media that the Hunley had been found. As stated above, it wasn’t true. Both the State’s GPS coordinates (which had been furnished to them by Cussler) and my location (as shown by the “X” on my map that I had published in my book well prior to Cussler’s alleged discovery) for the wreck are beneath the small red dot shown within the yellow outlined “Hunley Protection Zone” that was maintained by the Coast Guard during the raising of the Hunley.

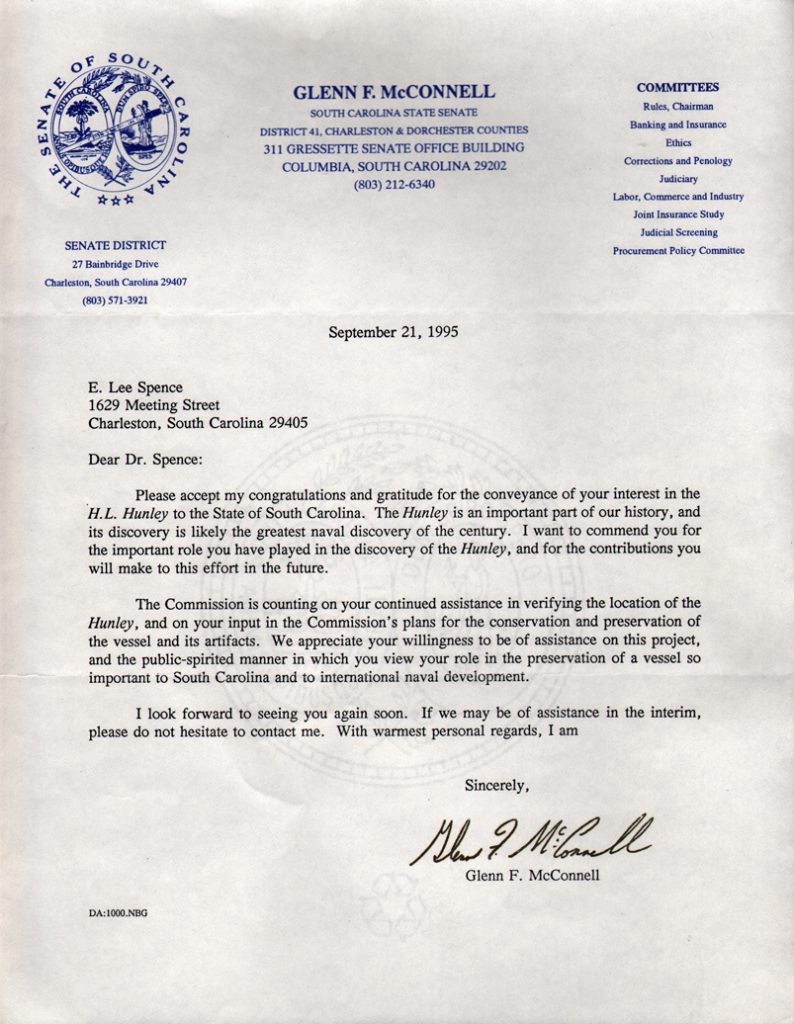

At that time, the president of the South Carolina senate was Senator Glenn McConnell, who was an ardent student of the Civil War and, in response to his and the public’s sudden interest, the State legislature passed a law to set up the South Carolina Hunley Commission to take control of everything related to the wreck.

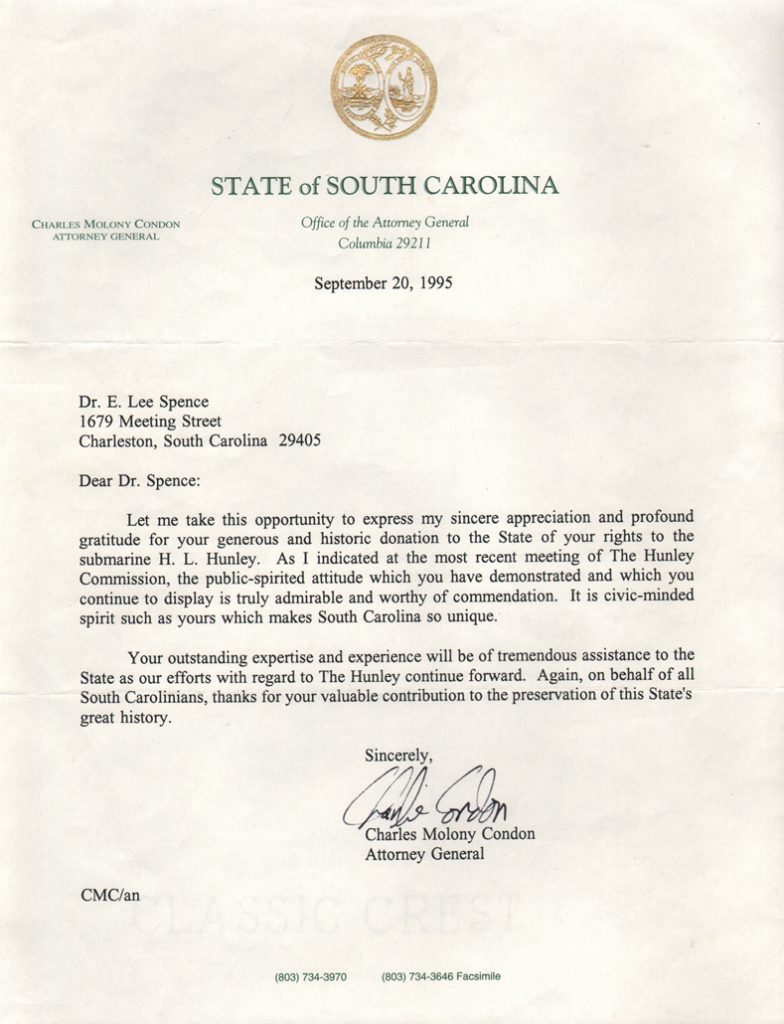

On September 14, 1995, after a review of my 1980 court filing and other documents by South Carolina Attorney General Charles M. Condon, who agreed I had not only discovered the wreck but was its legal owner, and at the official request of Senator Glenn McConnell, Chairman of the South Carolina Hunley Commission, I donated my rights to the Hunley to the State of South Carolina. Here are both of their letters.

Attorney General Condon has never wavered from his support of me as the discoverer of the Hunley and, while he was still in office he did his best to see that I was properly credited.

The author of this letter was the president of the South Carolina Senate and Chairman of the Hunley Commission. He was the one who asked me to donate my rights to the Hunley to the State, which I did. The Senator failed me more than anyone and I am convinced that he helped Cussler get credit for discovering the Hunley because he feared the damage that Cussler could do to his career if the $100,000 Cussler threatened to give to his opponent was used to investigate rumors about the Senator.

Shortly after I signed over my rights to the Hunley to the State, and the Hunley Commission asked me to lead another SCIAA expedition out to the site, a reporter asked Cussler what he thought about it. Cussler reminded the reporter of his promise to give $100,000 towards the raising of the Hunley and said that if the Hunley Commission didn’t do what was right (presumably he meant credit him), he was going to write the check instead to Senator McConnell’s political opponent. Senator McConnell was chairman of the Hunley Commission and Cussler’s threat must have worked, as the next time I talked with Senator McConnell, I was told that I would not be leading the expedition. Soon after I was informed that I wasn’t going to be allowed to even participate in the expedition and that if I went to the site, I would be arrested and my equipment confiscated. I also learned that Senator McConnell was crediting Cussler with the discovery.

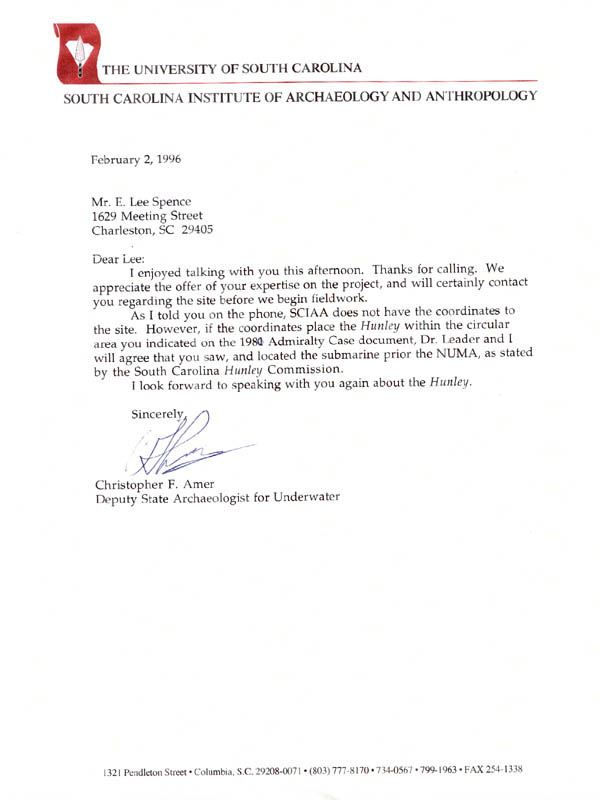

Seeing the writing on the wall, I contacted the State Underwater Archaeologist Chris Amer at SCIAA to be sure that I would be properly credited. Amer assured me in letter typed on SCIAA letterhead that both he and the State Archaeologist Dr. Jonathan Leader would credit me with the discovery if the wreck was proved to be within the area I had filed with the U.S. District Court in 1980. There is absolutely no question that the wreck was within that area.

Despite this 1996 letter with Chris Amer’s assurances that he and Dr. Leader would credit me with the discovery of the Hunley, if the wreck was determined to be within the area that I had filed with the Federal Court in 1980, which it was, neither man honored it.

Whatever their actual reasons, which I am unfortunately not privy to, despite the accuracy with which I had mapped my discovery, neither Amer nor Dr. Leader honored that written assurance to credit me. In a way I was not surprised that they did come through for me. When it had looked as though Dr. Leader was trying to take back control of the Hunley from the Hunley Commission, which incidentally really should have been in his hands, Senator McConnell had threatened to pull SCIAA’s funding, and not just that related to the Hunley. In effect, their jobs were on the line. Dr. Leader later told a reporter that I had probably mistaken an object, believed to be a buoy once used to mark the Housatonic’s location, for the wreck of the Hunley. But, since I had drawn and annotated a diagram of the rivet pattern of that object on a chart that I had personally provided Dr. Leader even before Cussler shared his GPS location it should have been clear from my annotations that although I was unsure exactly what that particular object was, I absolutely did not think it was the Hunley.

A couple of months after the Hunley was raised in the summer of 2000, SCIAA finally released the Hunley’s GPS location and it was scientifically determined by GIS expert Kevin Remington at the University of South Carolina that the “X” (for the Hunley’s location) on my chart, which I had furnished the State and Federal agencies decades before and had published in my 1995 book, closely matched NUMA’s GPS location. In fact, even though I had used a magnetic compass and a World War II era sextant to determine the wreck’s location, the center of my “X” when plotted on the standard nautical chart of the area, fell within 21-thousandths of an inch of SCIAA’s GPS numbers. That was far better than I had expected as, out on the ocean, that was the equivalent of less than the length of the salvage barge that had been used in the raising of the Hunley.

In 2001, Cussler’s organization NUMA sued me for slander for saying in a talk before at a Charleston museum that NUMA had not discovered the Hunley, and for saying that the SCIAA/NUMA 1995 Hunley Expedition had used my information to find the wreck. I immediately countersued alleging that, as a way to promote the sale of his books, Cussler was falsely advertising that he and NUMA had discovered the wreck of the Hunley, when in fact I had found it in 1970.

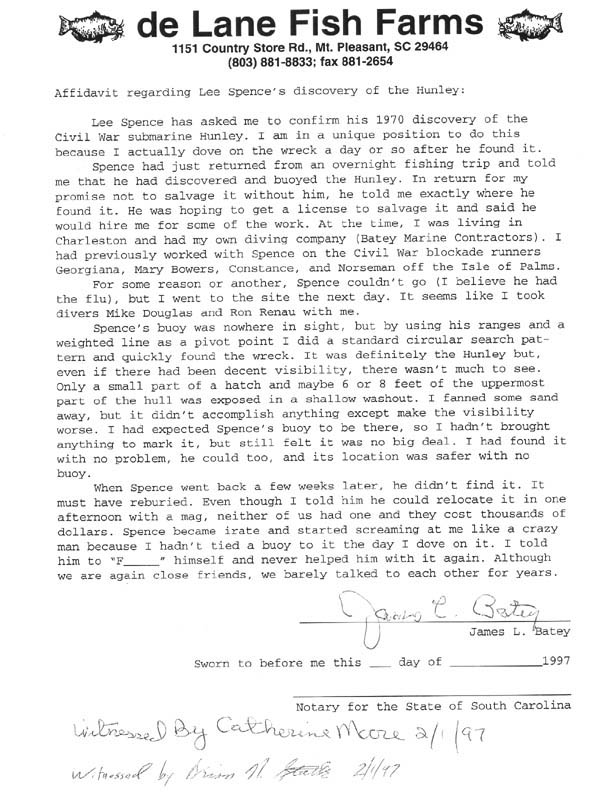

My claims were later backed up by Dr. Newell, who, even according to Cussler, had been the official director of the 1995 SCIAA/NUMA expedition to the Hunley. Dr. Newell gave a videotaped, sworn deposition acknowledging that he used charts and other information that I had previously filed with SCIAA to plan the expedition and that he believed I had found the Hunley in 1970. Newell credited his expedition with making the first verification that what I had found was indeed the Hunley. Dr. Newell was technically incorrect, as commercial divers Jim Batey, who now does sidescan sonar work for FEMA and other departments, and the late Ron Reneau, both dove on the wreck shortly after I discovered it in 1970 and confirmed it was indeed the Hunley. In 1996, in support of my efforts to be properly credited with its discovery, Batey gave a sworn statement detailing the dive he and Reneau made on the wreck. What Dr. Newell’s expedition did was to make the first “official” verification of the discovery, which I believe was extremely important. Incidentally, Dr. Newell also swore that after the controversy over who discovered it came up, he was told one of his supervisors to destroy all documents supporting my discovery claim. Fortunately, Dr. Newell did not follow those orders.

Affidavit by Jim Batey about his diving on the Hunley shortly after its discovery by Spence. It describes how little of the wreck was exposed.

Cussler, in a sworn deposition admitted that he never dove on the Hunley and was never on the boat in 1995 when he claimed the discovery was made. Upon further questioning about what constituted discovery, Cussler made it clear that he believed each person who saw something for the first time had discovered it, regardless of how many others had seen it before. Cussler’s definition of what constitutes a discovery is certainly not mine, and I doubt it’s the readers.

The documents in the above pictured boxes and folders all relate to the Hunley in one way or another. Without them I would have no chance of exposing the truth. With them, I can counter any virtually absurd claim that is made. I have well over 100,000 pages of documents and hope to one day leave them to a university or library.

After years of hearings and delays, my countersuit against Cussler and NUMA was thrown out on the basis that the statute of limitations for suing him for false advertising had passed before I filed my suit.

This U.S. News & World Report article, which was published in July of 2007, credited underwater archaeologist Lee Spence with finding the wreck of the Hunley in 1970.

NUMA’s suit against me could have gone on, but shortly after U.S. News & World Report’s July 2007 story on the Hunley, which credited me with finding the wreck in 1970, was published, and after the judge had made it clear that he would let me present evidence of my discovery to the jury, NUMA dropped their lawsuit against me.

As a result, a jury never actually got to view my evidence and settle the dispute. And until the question of who really discovered the Hunley is finally settled, the Hunley’s history will remain marred by fake news, propaganda and revisionist history.

.

See: IMPORTANT UPDATE

See also: The Discovery of the Hunley.