Ghost Galleons: Both Real & Imagined!

by Dr. E. Lee Spence

© 2010, 2018 by Edward L. Spence for composition and compilation

For most people, the term “Ghost Galleons” refers to legendary ships like the “Flying Dutchman” pictured above. But, for me it means shipwrecks that allegedly contain fabulously rich cargoes, but which have little or no basis in fact. Such shipwrecks can be a major headache to commercial salvors. The accounts of loss of the vessel may be grounded in fact, but the touted value or even the existence of the treasures they allegedly carried are not. Eventually, through gossip and legend, the phantom cargos of these ships become part of their accepted “history.” The more famous ones are sometimes reported (through ignorance or as part of a scam) as the targets of planned expeditions. Reams of material have been written about such “billion dollar” wrecks by serious but inept researchers, who, instead of doing their research using contemporary insurance records and government documents, sometimes rely largely on already published accounts. Even news accounts published contemporary to a loss can be heavily embellished, and later ones can be almost entirely fictional. Some “press releases” by unscrupulous individuals can even be an effort to sell investors on an outright fraud. And, since the sought-after treasures may never have existed, years of time and millions of dollars can be wasted in futile efforts to find and salvage them. The people hurt are not just the investors, but the people in legitimate salvage businesses, who’s reputations can be destroyed, simply by association.

Potential salvors should be aware of such ghosts.

In the 1970s, diver Wade Quattlebaum (since deceased) reported finding two shipwrecks in a river near Georgetown, South Carolina. Quattlebaum refused to disclose the exact location, saying he feared claim jumpers.

He told a gullible press and an eager public that he had found the intact wrecks of two sixteenth-century Spanish galleons loaded with treasure. He claimed that he had already raised and hidden hundreds of pounds of gold coins. His story was rife with mystery and intrigue.

My first reaction was that his story was complete BS, and I should have stayed with that. But, Quattlebaum won me over when he produced evidence that the State Archaeologist, a man who I already had a reason to dislike, was trying to cheat him out of whatever it was that he had found. The State Archaeologist, who obviously believed Quattlebaum’s story, had refused to issue him a permit and had instead contracted with an out-of-State group to search for the mystery galleons, which he thought could be found with the info Quattlebaum had already disclosed. Quattlebaum refused to provide me with proof of his discovery saying he had already made that mistake with the State Archaeologist. I could accept that and to me he seemed to be just a poor, uneducated man fighting for his rights. Despite the inconsistencies and contradiction in what I had heard about his wrecks, I unwisely believed him and tried to help. Both old and new friends (myself included) backed Quattlebaum with their reputations, money, time and equipment. I don’t know about the others, but the support I gave him cost me dearly. During the time I was trying to help Quattlebaum secure rights to his “wrecks,” I neglected my own business and almost went bankrupt. I lost a relatively new, six-bedroom home, both cars, both salvage vessels, and my wife left me. Fortunately, that was years ago and I have since found lots more treasure, bought bigger boats and houses and, although she has since passed, I met the love of my life and had a very happy and successful marriage.

Quattlebaum, who went on to sell used cars for a living, never produced the gold or the wrecks. Years passed and bits and pieces of the truth slowly came out. I finally came back to my original conclusion that the whole story was pure bull. There is not an ounce of doubt in my mind. His gold was only guano. Quattlebaum had simply lied to his family, friends and foes alike. He used me for credibility, others for for their wallets. His treasure galleons were ghost galleons. They existed solely in Quattlebaum’s fertile mind. That is not to say that treasure galleons don’t actually exist. He simply never found any. All he had done was to read extensively about them and use bits and pieces of their real stories to create a fictional one to support his fraud. The only gold coins he ever showed me were reproductions. They were exactly like ones that used to be sold at a treasure museum in Florida. I quit dealing with him the first day I saw them. Although I later saw some genuine silver coins that Quattlebaum had given friends (read potential investors), they were cheap ones from the wrong century.

Despite (or more likely because) of his past lies, Quattlebaum later convinced investors to back him in a venture seeking the treasure of what many incorrectly believed was another ghost galleon, the gold rush steamer Central America. Treasure hunters (including experts such as the late Mel Fisher) had long believed that the Central America had been lost in shallow waters off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. But it wasn’t. Their failure to find it after spending millions of dollars had almost relegated it to the status of a ghost galleon.

Through my research, I determined that the Central America had not wrecked off Cape Hatteras, but had instead wrecked in literally thousands of feet of water off South Carolina. I had shared my conclusions with Quattlebaum, who accepted my explanation that the wreck was off South Carolina. But, probably because he figured no one would back him on a project that deep, he later filed papers in the Federal District Court claiming to have discovered the wreck in less than two hundred feet of water. Fortunately, before his financial backers had spent too much money, another group announced that they had discovered the wreck. The Central America definitely wasn’t a ghost galleon, and it was exactly where my research had placed it. My theory on its correct location had been shared by another of my former business associates, without my prior knowledge, with Tommy Thompson who spearheaded the successful expedition and who, before finding it, had offered me a percentage of the treasure for my research.

Incidentally, Quattlebaum later made national news by selling high-priced (but apparently worthless) drug detectors to various law enforcement agencies. Even now, long after he died, Quattlebaum has thousands of fans who still believe that his ghost galleons are real.

After finding the wreck salvor Greg Brooks claimed the steamer Port Nicholson, pictured above, carried a large cargo of platinum ingots.

The wreck of the SS Port Nicholson made international news when, in 2012, a salvage company announced its discovery and claimed the steamer had been carrying a valuable cargo of platinum, gold, and industrial diamonds when it was sunk on June 16, 1942, by two torpedoes fired from German submarine U-87. According to news accounts, the treasure, which would have been worth billions today, had been meant as payment from the Soviet Union for material delivered under lend-lease. Investors are said to have poured over $8,000,000 into the company, Sub Sea Research, in support of the salvage venture. But, the documents listing the platinum were later shown to have been altered and the people involved were publicly accused of fraud. It seems that what the Port Nicholson was really carrying was just a cargo of automobile parts and military stores.

Another ghost galleon was the brig Nancy, reported to have sunk near the entrance to Winyah Bay in 1817 while traveling “in ballast” with specie (coins). The original report which appeared in the Charleston Courier was complete with a wealth of details, including an account of the heroic efforts of the crew to swim to shore. Just days later the story was discounted as a complete fabrication.

An unsubstantiated account of a wreck near Otter Island, South Carolina, in 1814 was later attributed to a deserter trying to gain safe passage to Charleston.

The report of the grounding of the ship Golconda near at Tybee, Georgia, in 1838 was afterwards found to have been an error and the account was retracted.

One intriguing “ghost” is the phantom dory which was seen at 2:00 a.m. on August 27, 1911, by several members of the Carolina Yacht Club who were caught at the club during the terrible hurricane which struck Charleston on that date. They reported seeing a dory, with full sail, coming towards the pier. Everyone thought that it was some member caught out in the storm, but just as it reached the landing, it disappeared. It was never seen again. It was later said to have been the ghost of the dories lost in the storm.

Some of the ships that really did carry treasure still belong in a sort of gray area alongside the list of ghost galleons. These would include wrecks that may have been salvaged at some point in the past, or that didn’t have any where near the amounts of treasure reported in modern books.

All of the coins shipped aboard the brig Lucinda, which was lost in 1806 near the Santee River while traveling “in ballast,” were saved at the time of the wreck, as was the $52,000 in face value in coin, which would be worth millions today, that had been aboard the brig Phoebe when it wrecked near Georgetown in 1838. Treasure hunters failing to do their research might incorrectly believe those wrecks still have all of their treasure.

Divers frequently say they want to search for the gold on the Civil War steamer Georgiana. Various accounts have been published stating that the Georgiana carried $90,000 in gold coin. There is even a novel that says she carried a giant ruby. The ruby was pure fiction but the gold was real and the total numismatic value of the coins would certainly be in the hundreds of million dollars today. But, records show that the Georgiana’s entire crew got off alive and even saved the mail. Some people might find it a little hard to believe that her crew would have passed up the gold to save a bunch of letters. Yet, the gold, if it existed, may have been hidden below tons of cargo where it would have been inaccessible to a fleeing crew. I discovered the wreck of the Georgiana and brought up tons of valuable artifacts, but I never found the gold. So, whether the Georgiana belongs in the lists of true treasure wrecks, or in a gray area next to the ghost galleons, is presently impossible to say.

Most people are aware that the majority of the ships carried merchandise or raw goods rather than gold or silver, but they frequently make the mistake of thinking that all vessels carried at least some sort of cargo which would have commercial value today. When found, these wrecks frequently become the source of stories of treasure.

Some vessels, like the Buena Vista, which was lost on St. Catherine’s Island in 1855, carried cargos consisting entirely of salt. Others, like the schooner Lucy Ann, wrecked in Long Bay in 1854, carried cargos of ice. But don’t necessarily rule them out as many such vessels also carried thousands of dollars in face value in gold and silver coins to buy more cargo, pay their crew, and pay other costs and fees. A very rare single twenty dollar gold piece from that time period recently sold for over $1,000,000.

It would be impossible to say if these ships would be a waste of time and money for someone just seeking treasure. But those wrecks, and others like them, are still of interest and importance to underwater archaeologists who see the remains of the ship itself as a treasure.

Many vessels were expected to be lost, but were later saved. Others were expected to be saved, yet were ultimately lost. Two vessels in the first category were the brigantine Spy, wrecked on Sullivan’s Island in 1759, and the steamer John G. Lawton, wrecked in the Savannah River in 1859. The seas were reported as beating over the Spy, and it was thought that it would be impossible to save her, but she was got off the following evening. The John G. Lawtonwas originally reported as a “total loss,” but was later raised, refitted, re-launched and described as “again in her element.”

The brig Pocahontas, which ran ashore south of Tybee, Georgia, in 1829, was in the second category– originally reported as having been saved, but later reported as bilged and expected to be lost. The schooner Ezra Wheeler, which was driven ashore on Folly Island, South Carolina, in 1842, was variously reported as “impossible” to get off, and as “probable” to get off.

Famous persons sailing from port never to be seen again have caused legends to grow up around certain wrecks, placing them in the category of ghost galleons. I have always been fascinated with the fates of Thomas Lynch and the beautiful Theodosia Burr Alston.

Thomas Lynch had been one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. Lynch was only thirty-two years old and was traveling through what is now known as the Devil’s Triangle when his ship disappeared without a trace. Lynch’s ship may have been sunk by a British privateer, or may have gone down in a storm. Some say it simply has never come to port and sails forever along with the most famous ghost ship, the Flying Dutchman.

Theodosia Burr Alston was the wife of South Carolina Governor Alston, and daughter of Vice President Aaron Burr (who killed his political rival, Alexander Hamilton, in a duel). In 1812, Theodosia sailed on the schooner Patriot, which disappeared without a trace. She was said to have been murdered by pirates and the schooner scuttled. However, some say the deserted vessel washed ashore in North Carolina in January of 1813, with no signs of violence. Food was still in her cupboards. No one knows what happened.

Vessels were sometimes reported as wrecking at one location, yet were subsequently found to have wrecked elsewhere. In 1779, a schooner with some sick and wounded American soldiers was thought to have foundered in a storm off Tybee, Georgia. It was later learned that she had been driven ashore below St. Augustine, Florida.

Such reports were often the result of speculation on the part of persons alive at the time of loss. Unfounded speculation can easily cause confusion, as can misinterpreted accounts of losses of vessels.

HMS Colibri was lost near the entrance to Port Royal Sound, South Carolina, in 1813. At least one modern account of that shipwreck shows the loss as having occurred near Port Royal, Jamaica. The author’s mistake was obviously due to the similar place names. Such errors can be costly and can wrongly place a ship in the category of a ghost galleon.

The 1760 wreck of the snow (variation of a brig) Anne, which is thoroughly documented in contemporary South Carolina papers as having taken place on the Charleston Bar off Morris Island, South Carolina, was shown in the London papers simply as having occurred on “the Bar of Carolina.” One modern author, apparently having read only the London accounts and making an educated guess or using sources I have yet to see, gives the location of the Anneas on Cape Fear Bar, North Carolina.

One of the most enduring stories of gold (that is basically pure fabrication) being lost on a ship, is that of a million dollar payroll that was supposedly on the British frigate Hussar when that vessel was wrecked in 1780 in the East River off New York City. Although the minutes of a perfunctory court martial held by the Royal Navy into the loss of the frigate makes no mention of a payroll, which it would have had the payroll existed, the story has persisted. Despite the lack of any government documents supporting the existence of the gold, and despite the difficulty of diving in those waters, the rumors of gold, which made it into countless newspapers and books, have resulted in repeated salvage efforts over the past couple of centuries. Of course, all those efforts have failed.

The late, underwater archaeologist and author Robert F. Marx once published a list of “Fourteen Fabulous Still-Sunken Treasures” in Forbes FYI. One of the listed treasures, with an “estimated value” of “$25 to $50 million,” was said to have been aboard the British merchant ship Success when a hurricane sank it and four others in Charleston harbor on May 4, 1761. Having previously researched these wrecks and found absolutely nothing in contemporary accounts mentioning the gold, I am tempted to place this wreck in my growing list of ghost galleons. However, Marx was one of the world’s best known shipwreck experts, so there is no way I am going to dismiss the treasure as fiction just because I haven’t seen all of Marx’s sources. However, unless I see more than just his list, I wouldn’t recommend anyone investing even one dollar going after this particular “treasure.”

Hundreds of vessels, such as the Molly in 1760, were reported merely as “foundered at sea,” but why they foundered or what they carried was frequently not known. Even as recently as World War II, half sunk derelicts were a cause of mystery and concern. Floating in a giant wind-and-current-driven loop, they sometimes traveled back and forth across the Atlantic before finally running ashore or ramming another vessel and sinking with their cargos.

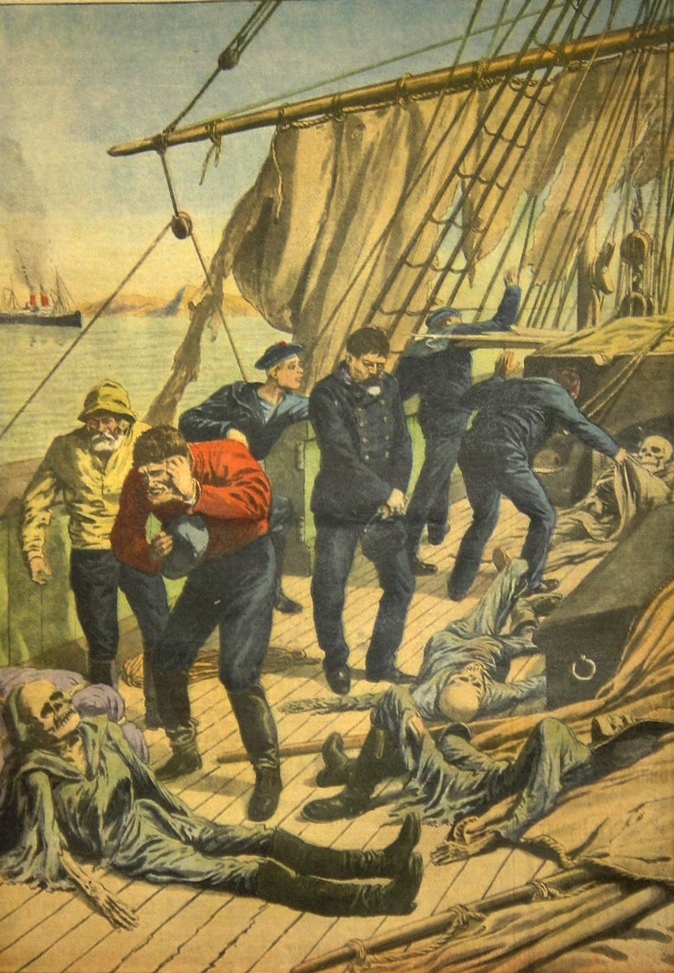

Imagine watching a full-rigged ship, with torn and tattered sails, pass within a few feet of your vessel without turning or signaling. As it almost runs down your own craft, you might curse the oncoming ship’s helmsman. But how would you feel if you suddenly saw that the helmsman was slumped over the ship’s wheel. And, if you knew you weren’t dreaming or hallucinating just think how would you might feel if you also saw corpses tied to the masts and in the rigging of the ship. Imagine seeing a vessel manned by the dead! You might cross yourself and wonder what damned them to such a fate. Did they die of hypothermia? A plague? Or, starvation? In centuries past, such sightings and causes were far more common than one might think.

High winds causing dangerous sea conditions, frequently prevented the boarding of these ghostly vessels. As a result, these ships were often allowed to sail on undisturbed. Some were reported week after week, month after month, ultimately traveling thousands of miles. When spotted by government vessels, derelicts were usually boarded and examined. Any dead found aboard were given hasty burials at sea and the vessels were scuttled or burned if they couldn’t be safely towed to port.

An apparition of HMS Eurydice, which sank off the Isle of Wight has been reported numerous times since its loss in 1878. Witnesses who would normally be considered reliable include a Royal Navy submarine in the 1930s and Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex, as recently as 1998.

The discovery of the dead aboard the sailing vessel Marlborough, as depicted by Le Petit Journal in 1913.

In 1913 major newspapers around the world carried accounts of the ship Marlborough, which had allegedly been discovered drifting off Cape Horn with the skeletons of her crew on board.

In 1885, the three-masted schooner Twenty One Friends, which was bound from Brunswick, Georgia to Philadelphia with a full load of lumber, was rammed by the John D. May off Cape Hatteras, and was abandoned by her captain and crew. But the ship didn’t sink and was after sighted numerous times over the next two years as she drifted around the Atlantic. She finally came ashore in Ireland, where both her cargo and the vessel were salvaged.

The sloop Emma and Eliza was found adrift in the Devil’s Triangle in 1840. She had no one on board. Her sails were partly hoisted and there were plates and food set on the galley table. There were no clues as to what happened to her crew.

Wrecks described in early accounts as in the “Gulph” or “Gulf” commonly referred to vessels lost in the “Gulf of Florida” or in the “Gulf Stream.” “Gulf of Florida” was the old name for the body of water in the gulf formed between Cape Fear, North Carolina, and peninsula Florida, as that entire coastline was once part of Spanish Florida. The Gulf Stream is the major current that flows through that area before it turns and runs across the Atlantic Ocean. Because of the confusion created by the use of the term gulf, these wrecks are often difficult to find. Many end up being incorrectly classified as ghost galleons. The crew of one such ship, bound from Jamaica, which foundered in the “Gulph of Florida” in 1757, was reported as having gotten safely to South Carolina. Salvors looking for her in the Gulf of Mexico would be wasting their time.

A number of years ago, salvors spent over $100,000 and almost lost the lives of two of their crew chasing a ghost galleon. They were hoping to salvage the World War II cargo ship Elizabeth Massey. They had found reports of her sinking (and approximate location) listed in several books on shipwrecks. The books reported that her cargo included over two thousand tons of copper. Checking government documents, they found that she had indeed carried copper on that voyage. Unfortunately, their research failed to spot an error made by the Coast Guard, which had incorrectly reported the event. The Elizabeth Massey didn’t sink. She simply participated in the rescue of the crew of another vessel (a tanker) which was lost. The Elizabeth Massey completed her voyage and delivered the copper without further incident. She survived the war and was eventually sold for scrap iron. A Tampa corporation, run by some of the same people who went on to run the publicly traded salvage company Odyssey, once promoted this “wreck” as a target. What a waste! I hope those who were involved are no longer going after such ghosts.

The steamer Golden Gate was lost off Manzanillo, Mexico on July 27, 1862, while carrying a fortune in gold.

The wreck of a California Gold Rush era steamer by the name of Golden Gate is another that some class as a ghost galleon. The 2,067-ton steamer caught fire and was run aground and burnt fifteen miles north of Manzanillo, Mexico, on July 27, 1862. At least 175 lives were lost. She carried at least $1,400,747 in coin and bullion, which would be worth at least fifty times that today. The reason some call her a ghost is that salvage attempts were started immediately and hundreds of thousands of dollars were salvaged, and they don’t believe anything is left. They have a point because of the large amounts that were reportedly salvaged and there was likely more salvaged than reported, but it is even more likely that she carried hundreds of thousand more than what was listed on her manifest. If that is true (and my gut says it is), she is not a ghost galleon and a fortune still remains to be found in the shifting sands around the wreck. The remaining gold could be well worth the high costs and risks of recovery.

In other words, don’t go after a wreck just because someone else has claimed that it carried treasure, and don’t necessarily dismiss another one just because someone else has described it as a “ghost galleon.” Do your own research and do it before you start your expedition. Draw your own conclusions and make sure that they are supported by the facts and not just by theories and opinions of others. Then, if your particular ghost ship starts looking real, go after it. Find the treasure and laugh at the skeptics.