There have been thousands of ships lost on a February 26, but one of the shipwrecks that stands out was that of the HMS Birkenhead, which set the example of “Women & Children First,” and was rumored to have carried three tons of gold coins. If you are reading this in a post, go to http://shipwrecks.com/shipwrecks-of-february-26/ to learn more about this shipwreck.

Today’s Shipwrecks™

February 26

compiled and edited by Dr. E. Lee Spence

1852: The steam frigate HMS Birkenhead was one of the first ships built for the British Navy that had an iron hull. Although initially intended for service as a frigate, she was converted to and commissioned as a troopship. She was wrecked on February 26, 1852, at Gansbaai near Cape Town, South Africa, while bound to Algoa Bay. It was reported that she carried 643 people and, as was too often the case, there were not enough serviceable lifeboats on board to save all the passengers. However, the soldiers, who were mainly from the 73rd Regiment of Foot, bravely stood by, allowing the women and children to board the boats first. Only 193 people survived.

The sinking of the Birkenhead is the earliest maritime disaster evacuation during which the concept of “women and children first” is known to have been applied. “Women and children first” subsequently became standard procedure in relation to the evacuation of sinking ships, in fiction and in life. The term “Birkenhead drill” became defined as courageous behaviour in hopeless circumstances and appeared in Rudyard Kipling’s 1893 tribute to the Royal Marines, “Soldier an’ Sailor Too”:

To take your chance in the thick of a rush, with firing all about,

Is nothing so bad when you’ve cover to ‘and, an’ leave an’ likin’ to shout;

But to stand an’ be still to the Birken’ead drill is a damn tough bullet to chew,

An’ they done it, the Jollies — ‘Er Majesty’s Jollies — soldier an’ sailor too!

Their work was done when it ‘adn’t begun; they was younger nor me an’ you;

Their choice it was plain between drownin’ in ‘eaps an’ bein’ mopped by the screw,

So they stood an’ was still to the Birken’ead drill, soldier an’ sailor too

Although contemporary news accounts don’t mention the loss of any treasure, the Birkenhead was rumored to be carrying a military payroll of £240,000 in gold coins weighing about three tons, which had been secretly stored in the powder-room before the final voyage. Numerous attempts have been made to salvage the gold. In 1893, the nephew of Colonel Seton wrote that a certain Mr. Bandmann at the Cape obtained permission from the Cape Government to dive the wreck of the Birkenhead in search of the treasure. A June 1958 salvage attempt by a renowned Cape Town diver recovered anchors and some brass fittings but no gold.

In 1986–1988, a combined archaeological and salvage excavation was carried out by Aqua Exploration, Depth Recovery Unit, and Pentow Marine Salvage Company. Only a few gold coins were recovered, which appear to have been the possessions of the passengers and crew. The rumored treasure and the shallow depth of the wreck at 98 feet (30 meters) have resulted in the wreck being considerably disturbed, despite its being declared a war grave. In 1989, the British and South African governments entered into an agreement over the salvage of the wreck, sharing any gold recovered. (Note: That’s important because it shows that both these governments want and are willing to share salvaged gold, even when it comes from a “war grave.”)

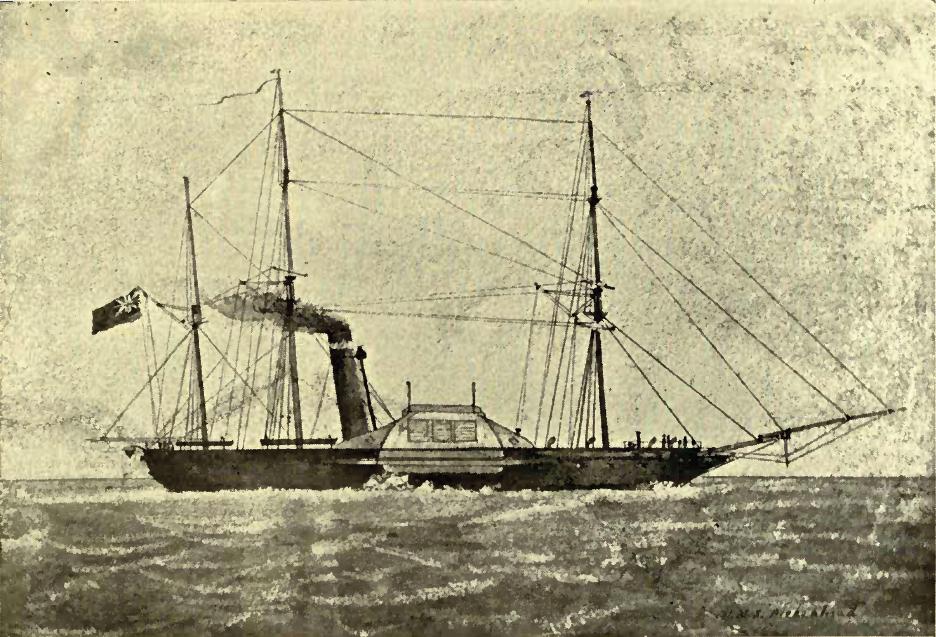

The Birkenhead was laid down at John Laird’s shipyard at Birkenhead in Merseyside, England, as the frigate HMS Vulcan, but was quickly renamed for the town where she was built. She had two 564 horsepower (421 kW) steam engines from Forrester & Co that drove a pair of 20 foot (6-meter) paddle-wheels, and three masts. As part of her conversion to a troopship in 1851, a forecastle and poop deck were added to the Birkenhead to increase her accommodation. She was initially meant to be brig rigged, but a third mast was added to change her sail plan to a barquentine. Although she never served as a warship, she was faster and more comfortable than any of the wooden sail-driven troopships of the time.

Shortly before 02:00 in the morning on February 26, while the Birkenhead was travelling at a speed of 8 knots (15 kilometers/hour), the leadsman made soundings of 12 fathoms (22 meters). Before he could take another sounding, she struck an uncharted rock at latitude 34°38’42” South, longitude 19°17’9″ East with 2 fathoms (3.7 meters) of water beneath her bows and 11 fathoms (20 meters) at her stern. The rock lies near Danger Point (today near Gansbaai, Western Cape). Barely submerged, it is clearly visible in rough seas, but it is not immediately apparent in calmer conditions.

Captain Salmond rushed on deck and ordered the anchor to be dropped, the quarter-boats to be lowered, and a turn astern to be given by the engines. However, as the ship backed off the rock, the sea rushed into the large hole made by the collision and the ship struck again, buckling the plates of the forward bilge and ripping open the bulkheads. Shortly, the forward compartments and the engine rooms were flooded, and over 100 soldiers were drowned in their berths

The surviving soldiers mustered and awaited their officers’ orders. Captain Salmond ordered Colonel Seton to send men to the chain pumps; sixty were directed to this task, sixty more were assigned to the tackles of the lifeboats, and the rest were assembled on the poop deck in order to raise the forward part of the ship. The women and children were placed in the ship’s cutter, which lay alongside. Two other large boats (capacity 150 each) were manned, but one was immediately swamped and the other could not be launched due to poor maintenance and paint on the winches. This left only three smaller boats available.

The surviving officers and men assembled on deck, where Lieutenant-Colonel Seton of the 74th Foot took charge of all military personnel and stressed the necessity of maintaining order and discipline to his officers. As a survivor later recounted: “Almost everybody kept silent, indeed nothing was heard, but the kicking of the horses and the orders of Salmond, all given in a clear firm voice.”

Ten minutes after the first impact, the engines still turning astern, the ship struck again beneath the engine room, tearing open her bottom. She instantly broke in two just aft of the mainmast. The funnel went over the side and the forepart of the ship sank at once. The stern section, now crowded with men, floated for a few minutes before sinking.

Just before she sank, Salmond called out that “all those who can swim jump overboard, and make for the boats”. Colonel Seton, however, recognising that rushing the lifeboats would risk swamping them and endangering the women and children, ordered the men to stand fast, and only three men made the attempt. The cavalry horses were freed and driven into the sea in the hope that they might be able to swim ashore.

The soldiers did not move, even as the ship broke up barely 20 minutes after striking the rock. Some of the soldiers managed to swim the 2 miles (3.2 km) to shore over the next 12 hours, often hanging on to pieces of the wreck to stay afloat, but most drowned, died of exposure, or were killed by sharks.

Share