The RMS Lusitania with its loss of almost 1,200 lives in 1915 is undoubtedly the most famous shipwreck that took place on a May 7. But the American gold lost aboard the German steamer Schiller in 1875, in relatively shallow water, is what has many people intrigued. The low end estimate of the gold’s worth today is over $17,000,000. If you are reading this in a post, go to http://shipwrecks.com/shipwrecks-of-may-7/ to learn more about some of the many shipwrecks that have occurred on this day over the years.

Today’s Shipwrecks™

May 7

compiled and edited by Dr. E. Lee Spence

1781: Three British ships, the Duke of Athol, Jenny and Peggy, and Nelly, were driven ashore in Riga Bay (Gulf of Riga, Latvia) on May 7, 1781.

1786: The Prussian vessel Zonsderdorf, bound from Liverpool, England, to Königsberg (present day Kaliningrad), Russia, foundered on the Dogger Bank. Her crew was saved. Note: The Dogger Bank is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about 62 miles off the east coast of England.

1804: The American schooner Blake, Captain Smith, bound from Combahee, South Carolina, with 200 tierces of rice, went on shore on Cumming’s Point on Morris Island, South Carolina, on May 7, 1804, and was believed to have gone to pieces in a severe storm on the following day. (Note: A tierce was a 42-gallon barrel.)

1810: The British schooner Sarah Milnor, Captain Cracklow, of Kingston, Jamaica, and bound from Havana, with a cargo of logwood and mahogany, was driven ashore on the beach of Morris Island, South Carolina, on the night of May 7, 1810, and was lost. Her crew was saved.

1818: A large ship was seen on shore five leagues to the westward of the Isle of Pines, Cuba, on May 7, 1818.

1822: The vessel Favorite, Captain Webster, from Honduras to Boston, was on shore and bilged near Edgarton, on May 7, 1822. Edgartown is a town located on Martha’s Vineyard in Dukes County, Massachusetts, United States.

1824: The vessel Aimable Eulalie, Captain Alleaume, from Guadelupe to Havre, wrecked on Anegada Shoals on May 7, 1824. A small part of her cargo was saved.

1833: The vessel Harriet, Captain Ross, bound from Liverpool, England, to Mobile, Alabama, was lost at Riding Rocks, Bahamas on May 7, 1833. Her crew was saved.

1834: The British full-rigged ship Rebecca, bound from London, England, to Quebec, Canada, with a valuable cargo, was sunk on May 7, 1833, by ice near the “Green Bank” off Scatarie Island, Nova Scotia. Her crew was rescued.

1839: The brig Lawrence, bound from “Cape Hayti” for Bristol, Rhode Island, “was stranded on Mayaguana Key” in the Bahamas prior to May 7, 1839. Her crew was saved.

1844: The American vessel Florida, Captain Crocker, bound from New York to Turks Island, was wrecked on Phillipe Reef, Grand Caicos, on May 7, 1844.

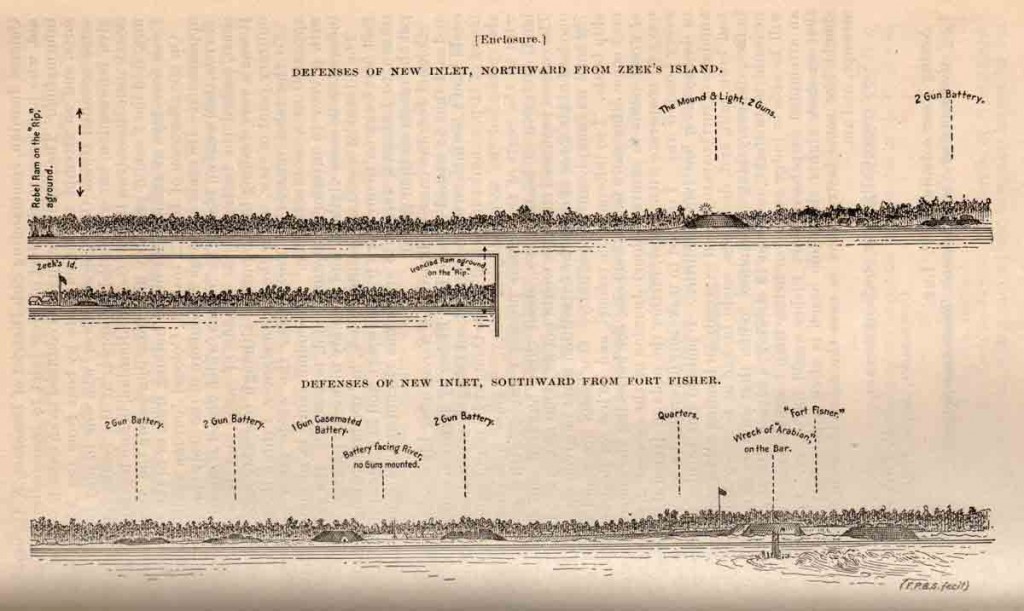

1864: On May 7, 1864, the Confederate States ironclad ram Raleigh, Flag-Officer William F. Lynch (or Lieutenant Pembroke Jones), crossed Wilmington Bar, North Carolina, and “attacked the enemy fleet, driving his vessels to sea.” The Federal vessels involved in the engagement included the Kansas, Mount Vernon, Howquah, and Nansemond. In returning to port, the Confederate ram got struck and “broke her back” on the New Inlet Rips (interior bar).

Sketch of the defenses of New Inlet showing the location of the wreck of the Confederate ram Raleigh and steamer Arabian.

The above illustration from Volume 10 of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of Rebellion, published in 1900, shows the position of the wrecked ram. It also shows the wreck of the blockade runner Arabian. One contemporary account described her as “a monstrous turtle stranded and forlorn” Her position was also given as “ashore on Zeek’s Island.”

The Raleigh had been built at Wilmington, North Carolina in 1864, and was armed with four guns. An eyewitness described her as follows: “The appearance of the vessel, is like a large vessel cut down to the waterline, and a house built on and plated. The sides of the house are arched, and having three ports on a side and one in each end. She has one smokestack and a small flag posted aft. Goes, I think, 6 to 7 knots, and turns very quickly. The guns fired at us during the night were not heavier than 30-pounders, but this morning she used much heavier ones; some think 10 inches.” She drew about 10 feet of water.

1864: Shortly before noon on May 7, 1864, while the USS Shawsheen was anchored close to the shore near Turkey Bend, James River, two miles above Chaffin’s Bluff, Virginia Confederate infantry and artillery surprised and thoroughly disabled the ship. Her commanding officer reluctantly hauled down her colors. Her crew was taken ashore in boats, and Shawsheen was set afire and exploded.

Confederate dispatches reported that she had “incautiously or defiantly approached” the Confederate position, which was secured with four Napoleon guns and two 24-pounder howitzers, and four companies of infantry. The Confederate fire was so brisk that her men were unable to stay at her guns and return fire. Four officers and twenty-three men were captured and as many as eighteen were believed killed. At the time of her loss, Acting Ensign Charles Ringot was temporarily in command and he jumped overboard early in the fight to swim to shore. Ringot tried to return to the boat but drowned. It was said that the Confederates had “fired seven shots through the white flag before they ceased.” After the vessel was aground and riddled with shot, and her men had surrendered, she was boarded and burned by the Confederates. The fire set off the steamer’s magazine “consigning all to the wind and waves.”

The USS Shawsheen was a sidewheel steamer with a walking beam engine and was officially rated as a tug. She had been purchased under the name Young America, by George D. Morgan from S. Schuyler at New York for $20,000 on September 21, 1861. She had a wood hull and was 180 tons, 118′ in length, 22’6″ in breadth, and 7’3″ in depth of hold. She drew 5’6″ of water. Her battery consisted of one 30-pounder Parrott rifle, one 20-pounder Parrott rifle, and one 12-pounder Dahlgren rifled howitzer. The total cost of her repairs while in naval service was $44,760.12. She was built in 1855 at New York, New York, and her first home port was Albany, New York.

1865: On May 7, 1865, the steamer Sylph, bound from Hilton Head, with passengers and government stores, went ashore in the Savannah River, above and north of Fort Pulaski, which is below Savannah, Georgia.

1875: The German passenger liner Schiller, bound from New York to Hamburg, with 254 passengers, a highly valuable general cargo and a large quantity of gold coins, failed to see the Bishop Rock lighthouse and passing on its wrong side grounded on the Retarrier Ledges in the Isles of Scilly at ten o’clock in the evening on May 7, 1875. The steamer sustained significant damage, but not enough by itself to sink the large ship. The captain attempted to reverse her off the reef, pulling the ship free of the rocks but exposing it to the heavy seas which were brewing, which heaved the ship broadside onto the rocks three times, rupturing the hull, putting out her lights, and making the ship list dangerously. (Note: The Isles of Scilly are an archipelago off the southwestern tip of the Cornish peninsula of Great Britain.)

Panic broke out on deck and passengers fought to get into the lifeboats. It was at these boats that the real disaster began, as several were not seaworthy due to poor maintenance and others were destroyed, crushed by the ship’s smokestacks, which fell amongst the panicked passengers. The captain attempted to restore order with his pistol and sword, but before he could do so, the only two serviceable lifeboats were launched, carrying far less than their full capacity. These boats eventually made it to shore, carrying 26 men and just one woman. On board the ship the situation only became worse, as breakers washed completely over the wreck. All the women and children on board, consisting of over 50 people, were hurried into the deck-house to shelter them from the worst of the storm. But, it was there that the greatest tragedy happened. Before the eyes of the horrified crew and male passengers, a huge wave ripped off the deck-house roof and swept all of the women and children into the sea, where they were lost.

The wreck continued to be pounded all night, and gradually almost all of those remaining on board were swept away or died from hypothermia. The morning light brought rescue for a handful of survivors. Of her original 254 passengers and 118 crew, there were 37 survivors for a death toll of 335.

The Schiller was built in 1873 by Robert Napier and Sons at Glasgow, Scotland. She was 3,421 gross tons, 380 feet in length, 40 feet in breadth, 24 feet in depth of hull, and had a 550 nominal horsepower compound steam engine, and two masts rigged with square sails. She was owned by the German Transatlantic Steam Navigation Line.

(Note by ELS: The amount of gold she was carrying is unclear. One report said she carried 300,000 $20 gold pieces, which would have made the total $6,000,000 (or, based on the respective values of gold, well over $400,000,000 today) but that report also said the value was only 60,000 pounds sterling, which would only amount to a little over $17,500,000 today. There was probably additional money in the 250 bags of mail she carried.)

1896: The crew of the Canadian bark J.H. Dexter, 540 tons, which struck and broke up on the Hogsty reef in the Bahamas on May 7, 1896, while bound from Mobile, Alabama, to Rio Janeiro, Brazil, were carried to the port of New York aboard the British steamer Alene, from Kingston, Jamaica. Wreckage from the lost bark was afterwards reported as arrived at Fortune Island Bahamas. She was 137.4 feet in length, 32.2 feet in breadth and 18.2 feet in depth of hold. Note: Some sources give the date of her loss as May 5, 1896.

1915: The British fishing trawler Benington, Captain Bridge, was shelled and sunk in the North Sea 10 miles southeast of Peterhead, Aberdeenshire, Scotland by the German submarine U-39 on May 7, 1915, less than a week after she had escaped from another submarine. Her crew survived and were saved by a Norwegian steamer. (Note: Another report describes her location as 180 nautical miles southeast of Peterhead.)

The Bennington was built in 1890 by J.P. Rennoldson & Sons, at South Shields. She was 131 gross tons, 95 feet in length, 20 feet 4 inches in breadth, and 10 feet 6 inches in depth of hold, with a two cylinder, compound steam engine of 35 horsepower.

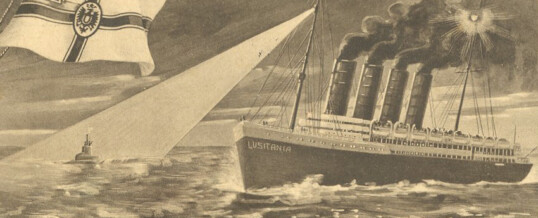

1915: The British Royal Mail Steamer Lusitania, bound from New York to Liverpool, was torpedoed by the German submarine U-20, commanded by Schwieger, on May 7, 1915 eleven miles off the southern coast of Ireland. The torpedo struck the Lusitania on the starboard bow, just beneath the wheelhouse. Moments later, a second explosion erupted from within the Lusitania’s hull. Almost immediately, the crew scrambled to launch the lifeboats. While the Lusitania carried more than enough lifeboats for all on board, the conditions of the sinking made their usage extremely difficult, and in some cases impossible due to the ship’s severe list. In all, only six out of 48 lifeboats were launched successfully, with several more overturning, splintering to pieces and breaking apart. Of the 1,959 passengers and crew aboard the Lusitania, 1,195 lost their lives.

When she left New York for Liverpool on what would be her final voyage on May 1, 1915, both her crew and passengers were well aware that submarine warfare had been intensifying in the Atlantic. Germany had declared the seas around the United Kingdom to be a war-zone, and the German embassy had even posted a warning in the newspaper, next to the advertisement for the steamer, not to sail in the Lusitania. And, when she was torpedoed the Lusitania was inside the declared “zone of war.” Although it makes no sense, some people later thought the British government actually wanted her to be sunk.

International law then required that, before opening fire on a non-military ship, warships were required to give the crew and passengers time to leave safely. U-20 had not followed this procedure because British merchant ships had been publicly ordered to ram surfaced submarines in violation of those same International laws, and because the Germans considered the Lusitania to be a legitimate military target in that the steamer was carrying munitions. Both the Americans and the British claimed the ship wasn’t carrying munitions. Regardless of who was correct, the sinking caused an international uproar led by the United States, which had lost 128 of her citizens. And, it caused a curtailment of German U-boat warfare for the next two years. Despite Britain’s initial claims that she was not carrying war munitions, she was and considerable munitions have been discovered on the wreck and even filmed in place in a widely published documentary.

The Lusitania was built by John Brown & Company Ltd., at Clydebank, Scotland, and was launched in 1907. She was 31,550 gross tons, 787 feet in length, 87 feet in breadth, and drew almost 34 feet. She had nine decks.

The wreck of the Lusitania lies on its starboard side at an approximately 30° angle in roughly 300 feet of water, 11 miles south of the Head of Kinsale Lighthouse, County Cork, Ireland. The wreck is largely collapsed onto her starboard side, due to the force with which she struck the bottom coupled with the forces of winter tides and corrosion in the decades since the sinking. The bow is the most prominent portion of the wreck with the stern damaged by depth charges. Three of Lusitania’s four giant 4-bladed propellers were salvaged by Oceaneering International in 1982.

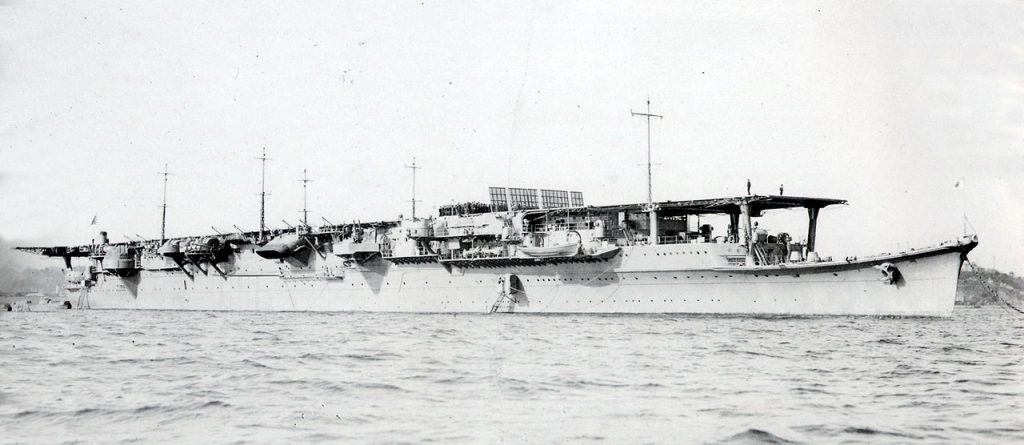

1915: The British Tribal-class destroyer HMS Maori struck a mine and sank in the North Sea off Wirlingen Light Ship, Zeebrugge, West Flanders, Belgium on May 7, 1915. She was built by William Denny & Brothers at Dumbarton, Scotland, and was launched in 1909.

The Maori was 900± tons, 255 feet in length, 25 feet 6 inches in breadth, and drew 8 feet 6 inches. She could make 33 knots. Her armament consisted of a pair of BL 4-inch guns, with one gun mounted on a small shelter deck forward and another on the quarterdeck, and two tubes for 18-inch torpedoes.

1942: The Japanese aircraft carrier Shoho, Captain Izawa Ishinosuke, and the rest of the Japanese fleet’s main force were spotted by aircraft from USS Lexington at 10:40. At this time, Shoho‘s combat air patrol (CAP) consisted of two A5Ms and one A6M Zero. The Dauntlesses began their attack at 11:10 as the three Japanese fighters attacked them in their dive. None of the dive bombers hit Shoho, which was maneuvering to avoid their bombs; one Dauntless was shot down by the Zero after it had pulled out of its dive and several others were damaged. The carrier launched three more Zeros immediately after this attack to reinforce its CAP. The second wave of Dauntlesses began their attack at 11:18 and they hit Shoho twice with 1,000-pound (450 kg) bombs. These penetrated the ship’s flight deck and burst inside her hangars, setting the fuelled and armed aircraft there on fire. A minute later, the Devastators began dropping their torpedoes from both sides of the ship. They hit Shoho five times and the damage from the hits knocked out her steering and power. In addition, the hits flooded both engine and boiler rooms. USS Yorktown‘s aircraft trailed those from USS Lexington, and the former’s Dauntlesses began their attacks at 11:25, hitting Shoho with another eleven 1,000-pound bombs by Japanese accounts and the carrier came to a complete stop. USS Yorktown‘s Devastators trailed the rest of her aircraft and attacked at 11:29. They claimed ten hits, although Japanese accounts acknowledge only two. As the Devastators were exiting the area, they were attacked by the CAP, but the Wildcats protecting the torpedo bombers shot down two A5Ms and an A6M Zero. Total American losses to all causes were three Dauntlesses. After his attack, Lieutenant Commander Robert E. Dixon, commander of USS Lexington‘s Dive bombers, radioed his famous message to the American carriers: “Scratch one flat top!”

Dramatic photo of the detonation of a 1,000-pound (450 kg) bomb on Sh0h0 during the Battle of the Coral

With Shoho hit by no fewer than 13 bombs and 7 torpedoes, Captain Izawa ordered the ship abandoned at 11:31. She sank four minutes later. Some 300 men successfully abandoned the ship, but they had to wait to be rescued as Japanese Rear Admiral Aritomo Goto ordered his remaining ships to head north at high speed to avoid any further airstrikes. Around 14:00, he ordered the destroyer Sazanami to return to the scene and rescue the survivors. She found only 203, including Captain Izawa. The rest of her crew of 834 died during the attack or in the water awaiting rescue. Shoho was the first Japanese aircraft carrier lost during the war.

The Shoho was an Imperial Japanese Zuiho-class aircraft carrier commissioned on November 30, 1941. She had two aircraft elevators and carried 30 aircraft. Her standard displacement was 11,443 tons. She was 674 feet in length, 59 feet 8 inches in breadth, and had a draft of 21 feet 7 inches. The ship’s primary armament consisted of eight 40-caliber 12.7 cm Type 89 anti-aircraft (AA) guns in twin mounts on sponsons along the sides of the hull. She also carried four twin Type 96 25 mm anti-aircraft guns.

1952: The passenger-cargo ship, SS James Lykes, en route from Norway to Mobile, Alabama, ran aground on the Matanilla Reef on the north end of the Bahamas, about 65 miles east of Fort Pierce, Florida, on May 7, 1952. The U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Pawpaw had responded to the report that the ship was “aground and taking on water,” thirteen miles east of Matanilla buoy, Little Bahama Bank.

• • •

NOTE: This is by no means meant to be a complete list of the vessels lost on May 7, as there have been thousands of ships lost for every day of the year. All of the above entries have been edited (shortened) and come from various editions of Spence’s List™. The original lists usually give additional data and sources. Those lists are being updated and are or will be made available for a fee elsewhere on this site.

© 2013, 2017 by Dr. E. Lee Spence for composition, content and compilation.

Share